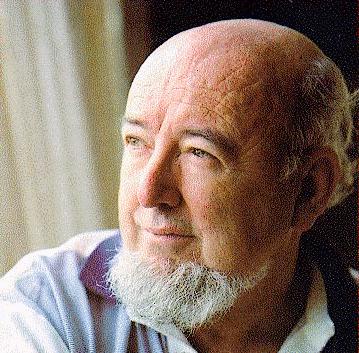

Interview with Thomas Keneally

source: Interview with Thomas Keneally

Broadcast: 25/05/2004

Reporter: Mark Corcoran

Transcript

KENEALLY: I don’t think Fred Hollows could believe if he were alive what has happened and I think he’d be over to Asmara to talk to Isaias in pretty straight terms.

(FOOTAGE OF KENEALLY IN ERITREA DURING CONFLICT)

CORCORAN: It seems that every war produces a literary work that defines the struggle and sacrifice. For the Eritreans it was Australian author Thomas Keneally’s book, Towards Asmara, a fictionalised account of the dramatic final years of the independent struggle in the late 80’s.

Thomas Keneally was a true believer who befriended Isaias Afewerke and shared his vision of an African Renaissance but even before the guns fell silent, discussion was dominated by how these fighters would manage the transition from a just revolution to a just republic.

KENEALLY: It is an extraordinary sensitivity they have to the perils of a revolution when it becomes a government.

Interview:

CORCORAN: Thomas Keneally, thanks very much for speaking to us today. You wrote Towards Asmara, a fictionalised account of the Eritrean struggle for independence some fifteen years ago, today are you surprised by the turn of events in that country?

KENEALLY: I can understand some of the paranoia that’s set in, if I can’t excuse it. It did seem the whole world was against these people. They didn’t want Eritrea to succeed and some people still don’t want it to succeed and it’s very hard to convince an Ethiopian that Eritrea isn’t part of his national birth rate.

CORCORAN: So what sort of man is Isaias Afewerke?

KENEALLY: Well we always saw him, when I say we, you know the supporters of Eritrea in the west who were also supporters of Ethiopia. They wanted to see an end to this mad war. They hoped that this revolution would be the sort of revolution that did not devour it’s children the way Robespierre devoured the children of the French Revolution in The Terror, including Danton... and we had great confidence in people like Isaias and so on but you know fighting wars and suffering the degradation of wars is not always the best preparation for creating a modern State and particularly so when the world is rather against you and that gets to you in terms you’re more and more paranoid.

CORCORAN: Well he’s locked up so many of his former comrades from the struggle, many others have fled into exile. Why? What’s gone on?

KENEALLY: Well it’s very human sadly to think that the revolution is one’s self when you’re as strong a person as Isaias.. and of course the whole thing about Isaias, there’s a kind of purity to him in a strange way, in that he was never... there were never posters of him anywhere. You know there is a monument of sandals. There’s no statue of him. You don’t see his picture on the street. As a student in Mao's China, he saw the cult of personality and abominated it. He lives in a modest house in a modest area of Asmara and so he is... if he’s a tyrant, he’s a pretty remarkable... he’s a departure from your average African tyrant.

CORCORAN: The Eritrean struggle if you like has been described as the “Spanish civil war of our times”, a great righteous, romantic struggle that captivated so many people, people like yourself, people like Fred Hollows. What was it that drew you in?

KENEALLY: The sort of things I wrote about in To Asmara where I talk about, there are these kids marching to school in bunkers and caves and they’re going to learn quite good mathematics and they’re going to learn literature and English and so on and they’re going to be taught often by amputee teachers who’ve served in the army and all the rest of it, and it doesn’t matter, these kids are skinny but it doesn’t matter if they’re going to die in two years of famine or bombardment, they’re still going to have the dignity of being literate and numerate and it was this acute sense of purpose. I remember above Keren, the city of Keren in 1989 passing out with heatstroke and when I came too in this stone bunker, I found that the bunker was full of young Eritrean soldiers with exercise books and it sounds corny but a medic said to me, now you’re feeling better Mr Tom, they called me Mr Thomas, now you’re feeling better Mr Thomas, could you tell us about the Australian electoral system. You know the franchise was so precious to them and I’m sure that it still is so that it’s a tragedy if the leadership now sits on that profound impulse which is in the Eritrean people, far more profoundly located then it seems to be in other African countries.

CORCORAN: Has it all passed the point of no return? Is the great African dream, this great African Renaissance, is it now dead? Is it now gone?

KENEALLY: I hope that it hasn’t. There are signs that it may.

CORCORAN: And how would that make you feel if it is the end?

KENEALLY: Well I don’t think my feelings are important because I’m a well fed westerner looking in from the sidelines. I think that the Eritreans that bore the noon day heat will feel betrayed.

CORCORAN: For Eritrea to have any hope in the future, will Isaias Afewerke have to go? Have to stand down?

KENEALLY: Yes I think he’s got to go back to what he said and believed in during what the Eritreans called “the struggle” or else he has to yield up government to someone who can institutionalise those democrat values.

CORCORAN: Thomas Keneally, thanks very much for speaking with us.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)