For Eritrean expatriate press, intimidation in exile

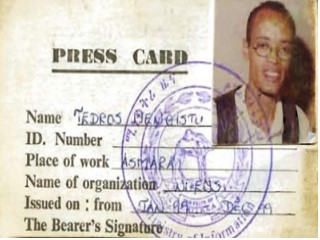

For the better part of the last 20 years, Tedros Menghistu has been a refugee, forced to flee his Red Sea homeland of Eritrea not once, but twice—first as a young man displaced by war in the early 1990s, and then as a professional journalist escaping political censorship and military conscription a decade later. Menghistu is also one of a handful of enterprising former professional journalists uprooted from Eritrea who have started independent news outlets in cities such as Houston, Toronto, and London. As outlets for a range of views suppressed by the government in Eritrea, these upstart media platforms work under intimidation from supporters of the Eritrean government.

For the better part of the last 20 years, Tedros Menghistu has been a refugee, forced to flee his Red Sea homeland of Eritrea not once, but twice—first as a young man displaced by war in the early 1990s, and then as a professional journalist escaping political censorship and military conscription a decade later. Menghistu is also one of a handful of enterprising former professional journalists uprooted from Eritrea who have started independent news outlets in cities such as Houston, Toronto, and London. As outlets for a range of views suppressed by the government in Eritrea, these upstart media platforms work under intimidation from supporters of the Eritrean government.

Menghistu arrived in Houston as a refugee in 2006. He works two jobs to feed his wife and two children while taking communication classes at a local community college. Since February 2009, he is also the publisher of a small community newsletter targeting Eritreans in southeastern Texas. “We’re working part-time; we print 250 copies and distribute in churches, Starbucks, and places where Eritreans gather,” said Menghistu, describing Selam, once a biweekly in the Eritrean capital of Asmara, and now a monthly newsletter distributed in Houston’s predominantly East African neighborhood of Lantern Village. “We intend to be a media platform for people to communicate with each other.”

“We also raise issues,” Menghistu added, referring in particular to an editorial that took a stand on the divisive issue of United Nations sanctions imposed on Eritrea in December 2009 on allegations that the country backs Islamist insurgents in neighboring Somalia. In this case, Selam’s editorial urged Eritrean expats to question their homeland’s government, rather than demonstrating against it, as heeded by the state and its supporters around the world, including in Houston. “One of the main reasons for the newsletter is to encourage people to express their opinions and at least tolerate other opinions,” Menghistu said. “Nobody should feel restricted to express themselves—for when you see a newborn baby, he or she cries, it’s a natural gift to express yourself.”

Easier said than done. “Wherever there are Eritreans, there are government spies who report your opinions and activities,” Menghistu said, adding that the supporters intimidate those opposed to the government with reprisals against family members left in Eritrea. “Those that have opinions different than the government, they are just labeled as opposition, as against the country, as traitors.”

Menghistu spoke from personal experience. On one Sunday in May, he went with his notebook and audio recorder in hand to cover a public seminar convened by local expat supporters of the Eritrean government to oppose the U.N. sanctions: “I was asked to leave the hall. I said, ‘Why? This is a public meeting.’ They said I had to go because I was not a supporter of [Eritrea’s ruling] PFDJ.” When Menghistu refused to budge, organizers allegedly turned the crowd onto him, stigmatizing him as “Woyanne” (a spy for Eritrea’s archfoe neighbor Ethiopia), and a traitor, among other insults. Menghistu was assaulted and his microphone stolen. He was treated for minor bruises at Houston’s Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital.

“I went to that meeting to try to cover what they were going to say,” he said. “I knew already what the meeting was about.” Houston’s police told CPJ they were investigating the incident, but Menghistu said some of the witnesses present appeared fearful to testify because they feared reprisals on relatives remaining in Eritrea.

One of those who relayed news about the Houston incident on his Eritrean diaspora news Web site was Amanuel Eyasu, once a senior editor with the state Eritrean News Agency and now the editor of the London-based site Assenna. To Eyasu, Menghistu’s account was more than familiar, he had lived it himself. It was in December 2007 when he filed a complaint with London police for assault after refusing to leave a public meeting of government supporters he went to cover. He documented the incident by posting an interview with one of the witnesses, a local Eritrean activist, who was also allegedly verbally abused and roughed up for his views.

One of those who relayed news about the Houston incident on his Eritrean diaspora news Web site was Amanuel Eyasu, once a senior editor with the state Eritrean News Agency and now the editor of the London-based site Assenna. To Eyasu, Menghistu’s account was more than familiar, he had lived it himself. It was in December 2007 when he filed a complaint with London police for assault after refusing to leave a public meeting of government supporters he went to cover. He documented the incident by posting an interview with one of the witnesses, a local Eritrean activist, who was also allegedly verbally abused and roughed up for his views.

The Houston incident was a front-page item in this month’s edition of Menghistu’s Selam newsletter, with a news article detailing it, an editorial, and a republished copy of CPJ’s news alert on it. However, Menghistu reported that the 200 copies he distributed in local stores earlier this month disappeared unusually fast. “One witness at a Starbucks told me he saw three guys—they came one by one, and took a large amount of copies. They collected everything.”

This development did not surprise Aaron Berhane, once the editor-in-chief of Eritrea’s defunct largest newspaper, Setit, and the publisher of the award-winning Toronto-based Meftih since September 2004. “They used to dump the paper in the garbage,” he said. “They flattened my car's tire with a knife on July 23, 2007. They broke the front glass of my car on January 17, 2008.” To overcome the sabotage of his paper’s distribution, Berhane said he convinced storeowners to install security cameras and relied on the assistance of volunteers.

Berhane and Menghistu experienced much worse when they were both involved in starting the first independent newspapers in Eritrea in the late 1990s. Menghistu, then a producer with state-run Radio Meneseyat (“Youth”), and a reporter with the ruling PFDJ's National Union of Eritrean Youth & Students (NUEYS) newspaper Tirigta (“Heartbeat”) said overwhelming political pressure in the state media made him want to start his own newspaper.

“Before we broadcast anything, a ruling party censor had to check everything,” he said. He recalled a time when he interviewed Justice Minister Fawzia Hashim about Eritrea's controversial presidential special court. “You had to give her the questions ahead of time and she had to read the story before it was published.”

Menghistu’s newspaper would be called Selam (“Peace”). It was 1999, during Eritrea's bloody border conflict with Ethiopia. “It was born in the middle of war,” he said. “I called it ‘Peace’ because people wanted peace.” Menghistu was also improving his training in journalism and shared workshop classes with Berhane and other journalists who have since disappeared in government custody. “I knew Dawit Isaac and Joshua [Fessehaye Yohannes]. We took courses at the American Embassy,” he said He still has a copy of an October 1999 story in Selam, reporting the attempt by independent journalists to create a private press association that the government would never allow. “We didn’t work long because in April 2000 they took us to military service.” He would escape only three years later.

For Menghistu, Berhane, and Eyasu, sustaining a news outlet only part-time while working odd jobs to survive is a personal expense and a demanding commitment on their personal lives. “I started Assenna with my own money in May 2007 and launched a shortwave to Eritrea radio station in February 2009,” Eyasu said. “I work eight hours for my day job, and the site is my night job. You do it at the expense of the time you can spend with your children, your personal life. You write the articles, you produce and post radio programs. Most of the time, I sleep at 3 a.m. and get up at 7. It’s demanding. When readers and listeners tell you you‘re doing good job, that’s our salary.” In Toronto, Berhane also runs Meftih part-time while working full-time as a market researcher.

All three journalists believe a lot remains to be done. “Media is very important for countries like us to become civil and gain political maturity,” said Eyasu. “We need lots of private media outlets representing a diversity of opinions and views. We’re not opposition per se; we oppose the government because it doesn’t allow any free existence of newspapers or things conducive to public debate. Even we oppose the opposition if they do similar things.”

For Berhane, diaspora media is a necessary outlet for the natural range of views of Eritreans that the government seeks to repress. Menghistu said that the Eritrean government knows the power of the diaspora media: “It has great potential to enlighten the people to know their rights and duties, and in the same token to stand up for their rights.” He went on to tell me with great frustration, “I lost two brothers in Eritrea’s war of independence and served in the military in the border war against Ethiopia. How could they treat me like an enemy of the country because I don’t think like them?”

For Berhane, diaspora media is a necessary outlet for the natural range of views of Eritreans that the government seeks to repress. Menghistu said that the Eritrean government knows the power of the diaspora media: “It has great potential to enlighten the people to know their rights and duties, and in the same token to stand up for their rights.” He went on to tell me with great frustration, “I lost two brothers in Eritrea’s war of independence and served in the military in the border war against Ethiopia. How could they treat me like an enemy of the country because I don’t think like them?”

Regardless, Menghistu is undeterred in his pursuit of journalism. “I have a long way to go,” he said, and told me about his long-term ambition of studying journalism at the University of Houston. But, he added, “I’ll continue what I’m doing.”

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)