Because red is our blood

Because red is our blood

In 1991, I walked the streets of my beloved city, Asmara, the center of our cherished country: Eritrea.

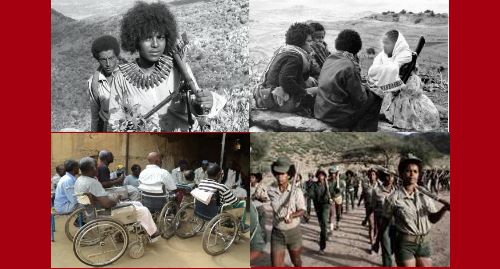

Our freedom fighters’ uniform was their humble smile. Their walks holding their weapons signaled the imminent collapse of the Ethiopian occupation. Free at last we were!

I will try – with this writing – to search for the patterns that destroyed this blissful image. We all were breathing deep, waiving to one another.

We all looked at our fighters as the liberators of evil. The streets I grew up and walked to and from school were back to me. To all of us.

What irrevocably changed my mind is when I saw a former fighter painting/covering the walls of the prison my husband was detained and killed at the hands of his torturers. Why would he “cover up” the only proofs we – the people of Eritrea- had about the unthinkable tortures that went on in those detention centers? Why the messages prisoners wrote with their own blood or bugs’ blood was covered now with white paint? I asked myself.

Something grew inside me, I refused to call it betrayal.

I tried to tell him about the streets and corners of Asmara covered in red Eritrean blood, with the nights’ killing from the notorious Ethiopian secret services. He said he had orders to follow.

I told him about the mutilated corpses we use to see everywhere throughout the city. He said he had orders to follow.

Eventually I reached his level of humanity and he and I sat on the grounds of the compound surrounding this particular place encircled by high walls covering the killing fields. I told him that in those fields surrounding what used to be the Ethiopian emperor’s summer residence, were now filled with remains of Eritreans – women and men alike - Some were forced to dig their own graves, large round pits that would be filled with corpses …some decapitated, pregnant women had their stomachs wide open with bayonets….how could you be told to cover up all this? I asked him. He stretched his hand and said “you are not a soldier on government’s pay”

I held his hand back. I wanted to find Berhane’s message on those walls, but my anger turned into pity and sorrow. It was too early to give up hope, I told myself.

This soldiers and I became friends. I will call him Alex.

He told me about his dreams during the liberation war. He told me he aimed at going back to school and offer an education opportunity to his wife as well, a freedom fighter herself. But now they had to put all on hold and feed the kids.

He always talked with no notes, but so eloquently about the mixed feelings he harbored in his heart. Beyond the summer’s night which seemed to stir his secrets and the crickets’ chirping, I saw a man thorn with doubts about the future of our country. We both could hear car doors slamming in the parking surrounding the restaurant’s ‘outdoor we were sitting at, but we both only concentrated on our dreams and the shutters closing fast around them. He asked me not to give up and not to make the cheap labor our people would go through the ultimate line of hope for all Eritreans. He saw already – in 1991 – the “cheap labor” our youth would be forced to live by. He told me his fear of the oligarchy and the need for continued resistance. I told him that while they – our fighters – were leading battles in the fields, the population – at times very young teenagers – were spreading the uprising with nothing more than stones or courage to put up pamphlets all over the cities’ walls. The Ethiopians shot to kill them with no mercy. Where his negativity was coming from, I asked.

From some elites’ thirst for power he replied. I nodded to that. He made me think about this quote: “We are all equal, but some are more equal than the others” Animal Farm – George Orwell

We were both sitting poised and we volunteered no question for one another, but only confided as Eritreans going through anxiety all while hoping to be wrong.

Alex told me that soon the private newspapers might go underground.

I took Alex’s fears to good friends of mine and high power holding people.

They all smiled and asked me for his identity. I left the part of wall painting out, for it would have been easy to find my friend Alex. Little appeared on national TV of Alex’s fears. I was so stressed about Alex’s predictions. Was it fear or knowing that he was not wrong? The flags- in my mind -I suppressed so many times refused to go away. I returned to Eritrea often and at each time Alex and I enjoyed coffee and exchanged hopeful ideas for this land we love so much.

As Pablo Neruda said “come and see the blood in the streets” but the blood was now being covered by my own country’s first government.

Eritreans came back from the diaspora, sold their properties and tried to settle back in the land they loved beyond words.

And here Alex was telling me that Freedom is already rusty and Oppression of the people at the horizon. How could that be? I asked him. All we still see at the horizon is the dust lifted by your plastic sandals and the sound of drums welcoming you in. What makes you say that our land and our sea will be red with our own blood? Is it not enough the blood of my Berhane and many like him that paid the price?

To my vexation and dismay I felt the same, but preferred to be in denial and trust my highly placed friends. They were holding power, they would fix it all I said. But my inner heart told me that Alex was not trivializing the very freedom he paid with his life.

Alex’s face was stern, tense and watchful of people around us.

That early he already analyzed and set a critical mindset not only for him, but for me as well.

One day – around late 1997- I walked to my friend Sherifo’s house. As always his smiling face and the tobacco he chewed continuously welcomed me in. I told him about these fears that I clearly made mine. Sherifo was always a man of few words. That day, he smiled broadly and told me not to fear. I asked him to stop the “mission” of covering the messages in all jails’ walls in Eritrea and turn those places into museums. He suddenly turned serious and said “I cannot for the moment”

“When then I asked? And why not now Sherifo “? I asked. He got up left and came back with no tobacco in his mouth. His eyes very serious and then he said “It will take much longer than I wish Kiki, but I ask you never to give up” I was more confused. We were sitting in his living room and suddenly my friend – and his neighbor Tegadalyt Miriam Ahmed- walked in. She saw our faces and asked if all was OK. I told her in few words what we were discussing and then I asked Sherifo “Is there a reason you cannot stop all this right now?” He said “The people of Eritrea need to be informed about major issues first. Building museums is not a priority right now”. We had coffee and I left.

I ask myself today if the “priority” the people of Eritrea had to be informed about was the issue of Badme. The war exploded few months later. Was my friend Sherifo talking about Badme? The wall cleaning, Alex’s predictions and Sherifo’s solemn statement of “informing the Eritrean people” are still creating confusion and pain to no end within me.

Today, my highly placed friends are placed in secret jails. Sheriffo included.

Young generations of Eritreans are perishing at high sea.

Eritrean women are laying their bodies for the pleasure of Bedouins in order to find a safe escape for their kids.

Eritrean Veterans are scattered all over the world and many wasted their lives to alcohol and drug abuse.

All this makes me ask: what price Eritrea?

The tears we cried. The pride we feel to this day, it all walks parallel with the sense of loss that follow us like a shadow of death we need to fight and defeat, by holding hands. By reaching out for each other. By owning mistakes and clapping at achievements.

By learning to be humble and never forget the reason our Martyrs paid the utmost price for. By uniting. By making Eritrea one.

Anger and pain can be an explosive formula for future generations.

We either bring them together by setting an example, or we will be the cause to dim the light of freedom.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)