Eritrea: The Usurpation of Christian Religious Power and Lexicon

Eritrea: The Usurpation of Christian Religious Power and Lexicon

Historians on Ethiopia and Eritrea have lately used the numerous gadla (biographies) of the saints as a resource in order to fill the missing gaps on the land tenure, economic and social history of the region. Whereas these historians are after real, authentic institutions and documents, this writer will discuss the gross misuse or perversion of the religious beliefs and concepts for the political agenda of the Eritrean liberation fronts, and particularly the EPLF, which is now the ruling power in Eritrea. Many writers have discussed about the extractive political and economic system of the current government, but have eschewed the mechanisms that were in place long before the fronts emerged as the victors.

The writers have rightly condemned the confiscation of land, the practice of slave labor, the decimation of private enterprises, the repression of human rights, and yet had been captives of the language, rituals and ceremonies of the regime. The trouble begun, and this also includes the Ethiopian left, when they started using the liturgical language Ge’ez for their revolutionary work. These radicals abhorred the old society and planned for the complete transformation of the society in which the new “socialist man” will reign. It was not out of nationalism, as some would like to put it, for what then explains their complete infatuation with the Marxist ideology of all stripes in the last century?

The fronts in Eritrea and Ethiopia proudly retell the Long March they made during the long years of their stay in the countryside famous for its ambas, steep mountains and hot arid plains without bothering to do any pilgrimage to the many monasteries. The gadams were the repositories of the old civilization. The affront in it is that the fronts often made the claim that they were doing research of the customs and economic livelihood of the communities in the rural areas, not excluding the botany. This has remained a bogus claim, however.

Had they embarked on a serious attempt to study the history of the region, assuming they had the training and curiosity, hundreds of studies would have been available for the public, which for almost three decades felt completely isolated from the region. There were many monasteries in Eritrea, which were the depositories of religion and cultural ethos of the people in the highlands, such as, Debre Bizen, Debre Libanos, etc. The revolutionaries were, however, oblivious to them. When they ventured into these sacred abodes, it was mostly out of material needs: food, drought animals, etc. They had neither the will nor the humbleness to ask and learn the history of the old Ge’ez civilization from the monks, whom they considered as the appendage of the “feudal” class. In the eyes of the radicals, the residents of these sacred places were as backward and superstitious as the large majority of the peasants, the gebars.

In Eritrea, the day of the armed rebellion and name of its Founders is quite known among its inhabitants and the writers, who chose the history of the region as their specialty. Ask, however, anybody about the origin and purpose of the use of the word “ghedli”, (derived from “gadla”, the language of liturgy of the Ge’ez-Rite religions), and chances are nobody has a given a thought about it. Is the use of this word, which means life or act of saints in English, an incidental borrowing of the fronts or a deliberate use of religious concepts for political propaganda? Within the habesha realm, in both Eritrea and Ethiopia, saints and the monasteries they belonged to have been places of pilgrimage for the poor, the infirm and the powerful nobility. There were also many instances when these same people would opt the vocation of the monk and join the members of the monastery for the rest of their life.

The appropriation of the religious term gadla for gedli, the strictly political project of the Eritrean armed struggle, which was violent and required the practice of a cult culture inimical to the values of monasteries, has resulted in the damage of the psyche of the Tewahdo Christians. The repercussion of this policy cannot be separated from the ongoing repression that the Tewahdo church, other Christian denominations and Islam have been suffering for the last several decades. The fronts, and particularly the EPLF, which were infatuated with the communist doctrine during the ghedli sojourn did not limit themselves to only extractive economic and political measures.

The traditional culture was also under attack for decades long before the forceful abdication and detention of Patriarch Antonios. The Church was not able to fight back for obvious reasons because the public space and the isolation it enjoyed disappeared once the armed rebels roamed most of the countryside. The behavior of the Church was contrary to the practice in the past wherein the public, including the nobility, were not spared from censure. For example, in the turbulent politics of the forties, politicians who did not endorse the unification of Eritrea with Ethiopia were excommunicated and denied religious burial ceremonies.

What then explains the copious use of many Tigrinya words derived or hacked from Ge’ez in the literature of the armed organizations? What is strange is that the same political actors, who hated and scorned the old traditions to the extreme, did not blush in exploiting the dead language. All the political actors in the turbulent 70s in Ethiopia on either the opposition side or the government side were in the frenzy of coining words with the help of Ge’ez words for political and economic concepts that originated in industrialized communities of both the liberal and the communist world.

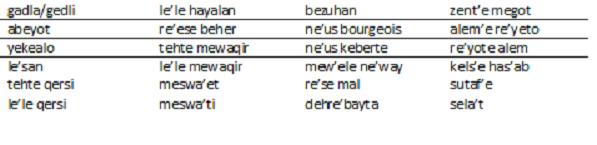

The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party, the All Ethiopia Socialist Movement and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front were churning out plenty of leaflets with equally numerous Ge’ez words interspersed between the Tigrinya and Amharic language. Their formidable enemy, the Derg, was also in the same habit. In short, all the political groups harnessed Ge’ez for their ill-conceived modernization. This state of affairs was exceptional for the time in which nearly all of the major political organizations were quick to point out the alleged mistakes of the other. Here are a few words compiled for the benefit of the reader.

Table 1

None, however, excelled the EPLF in the transferal of the Ge’ez liturgy for its own religion, that is, the totalitarian religion. Its audacity was when it adopted the sacred term, yekealo, or “omnipotent” for its leader, Isaias Afwerki, and by extension its organization. The farce in this journey is that, the EPLF, which had been viciously attacking the late Haile Selassie for claiming to be an elect of God only ended claiming the divine power for itself. The collaboration of the Tigrinya in Eritrea, their cousins in Tigray and Amhara regions in the emasculation of their Christian religion, institutions and the Tewahdo church was not that all different to what happened in the old Soviet Union.

A critique on the “passivity” and resignation of the Tewahdo church and other Christian denominations without a scrutiny of the ghedli’s past is insincere and unfair because the priests, deacons and custodians were the victims of political violence in the hands of the armed political entrepreneurs. The fact that they were the elite of the multitude of Christian highlanders made them an easy target in the eyes of the guerrillas, who did not tolerate any rival power center. Lastly, the Ethiopian Church itself was under siege, weakened and pauperized by the Derg having lost most of the land property, it could not lend support or solace. The Church’s power and influence decreased in an important way when the youth abandoned it in droves in search of some explanation for the suffering they obtained under the new regime of EPLF. Alas, this phenomenon preceded its belated tehade’so program.

The Tewahdo church in Eritrea was not what it was in the 1940s, when its power was at its apex. In an age, when the separation of power between the state and church was totally unknown among the inhabitants, the fact that it chose to rally for unity with the people in Ethiopia was later to earn it enmity, infamy and outright repression. Predictably, it was not strong enough to resist the emerging totalitarian power. It was not even strong enough to save its wulide kahnat (deacons and priests) from the clutches of drafting measures.

The fact is the Orthodox Church was in crisis throughout the ghedli times. The Church that admonishes its congregation in every sermon, pointing to what Christ said to the believers: “sick I was, you did not visit me, hungry I was, you did not feed me, under-clad, I was, you did not clothe me” [it is not a literal quote] had also been in a similar strait. When the fate of the Church was in question not many of the people, who now lament its condition, raised their voice. Infatuated with nationalism and Marxist ideology, they dismissed the Church as a timeworn obscurantist institution impeding the progress towards the sunshine on the hill. On hindsight, what the ghedli did towards weakening it was incomparably worse than even the pro-Islam Italian colonial policy and, subsequent to it, the Derg’s socialism.

The Tewahdo Church and the other Christian denominations, which depend on priests and deacons for their survival, were increasingly denied the novices needed to replace the weak and the old, for the state has usurped the right of the “mobae’” (offering, oblation) for its armed institution, and its civic religion . The Tewahdo Church and the others unwillingly abdicated their power to the yekealo princes, who did not blush to hear kibrin megosn n’e Hizabawi genbar (Glory and Praise to Hizbawi Genbar).

“The idea of transferal of the articles and symbols of one faith in being taken and adapted by a newer creed points in turn to Fascism’s ability to infiltrate the symbolic universe of Roman Catholicism,” wrote Charles Burdett for the Italy of Mussolini period. In a like manner, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front usurped and adapted Buddhist and Christian symbols respectively for a utopia. The State of Eritrea has now accorded itself the power of denying burial ground and Christian funeral rites to people it considers as either unpatriotic or not loyal enough.

The State of Eritrea had also likewise brazenly re-christened the scores of prisons in the land with the Ge’ez word tehade’so. These prisons are hellholes and completely inimical to the concept of the word. According to some reliable sources, nearly all of the kifle serawit of the Eritrean army has prisons attached to it under the same name. The State of Eritrea has corrupted the very word that the Tewahdo Church used to revive the spiritual belief of its followers. Its notoriety to this writer is however, when it coined the Ge’ez phrase, yohana, which has a clear religious meaning for the strictly public holiday, that is, the military victory in of the EPLF on May 24, 1991.

References

1. Kaplan, S. (1997), “Seen but not Heard: Children and Childhood in Medieval Ethiopian Hagiographies”, The International Journal of Historical studies Vol. 30, No 3, p.1.

2. Burdett, c (2003),”Italian Fascism and Utopia”, History of Human Sciences Vol. 16 No 93, p.4.

3. Ibid. p.95.

{jcomments off}

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)