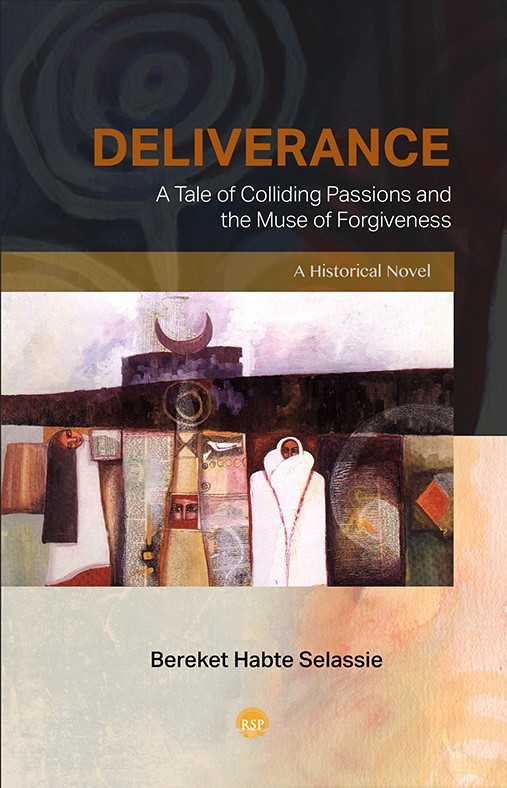

Book Review - DELIVERANCE: A Tale of Colliding Passions and the Muse of Forgiveness

Book Review

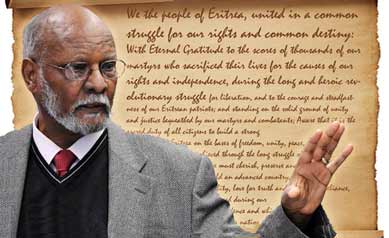

Bereket Habte Sellassie Dares to Dream

By Dawit Mesfin

DELIVERANCE: A Tale of Colliding Passions and the Muse of Forgiveness

A Historical Novel

by Bereket Habte Selassie

346 pp. The Red Sea Press.

The story Dr Bereket Habte Selassie presents in his latest book is about the tumultuous era during which I lived in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I can say that I found it, partly, the story of my youth, reminding me of how the bright and dark shades of the 1970s shaped my attitude and the positions I took in my personal life. The account took me back to an era I had stepped out of long ago and have tried to dismiss from my memory. But the vivid portrayal of that era readily conjured the image up and I came to realize that the characters, and the story itself, touched a nerve within me.

Both Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) and the All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (MEISON) were fervent leftist supporters of the Ethiopian Revolution that toppled Emperor Haile Selassie and abolished the monarchy in 1974. There were many Eritreans among them. Who can forget Amanuel Gebreyesus, Tesfu Kidane, Marta Mebrahtu, Yohanes Sebahtu, Amanuel Yohanes and more? The historical phenomenon of the student movement which was overtaken by the outbreak of the 1974 revolution and hijacked by the Derg, played a significant part in the intensification of the struggle to liberate Eritrea. The major part of Dr Bereket’s account revolves around the work of both the EPRP and MEISON and the era of the Derg’s Ityopia tikdem movement which ushered in a collective madness that affected all of us.

The ideological intoxication, courage, armed struggle, military ruthlessness, betrayal, youth anger and frustration, slaughter, flight to safety, life in the diaspora and more are movingly depicted by the various characters in the story. The Ethiopian revolution consumed so many young lives that my mind is seized with revulsion whenever it drifts back to that era.

On the other hand, the human stories depicted in the account are heart-warming, albeit sad. Dr Bereket captures the love of local cultures, love among human beings, love of God and of course, love of country. The depiction of the personal challenges people faced once bitten by the revolutionary bug is spot on. The accounts of ‘the underground days’ of the revolutionaries, their evolving consciousness during the internal fighting, the Derg’s open hostility towards them, the back-biting and betrayal among rivals is emotionally draining to read.

The story challenged my heart while my mind, which retains resentful memories of that era, tried to disown it as if it played no part in my life as an Eritrean. We Eritreans have always been staunchly loyal to our own cause. However, that commitment was so abused as to allow Isaias Afwerki to manipulate and hijack the youth spirit that sustained the struggle. I would argue, heavy-heartedly, that it suffices to look around us to see where that blind loyalty got us in the end.

Although the narrative invites the reader to remain open-minded as it turns into a dramatic play, the story that unfolds affected me deeply. I could see an old friend of mine who was kidnapped and harassed in broad daylight by government soldiers. They inserted EPRP leaflets into his leather notepad portfolio in front of him and then accused him of being an accomplice. They drove him to a secluded place under a bridge, stripped him of his watch and wallet and instructed him to bring a large amount of money the next morning. On that same day he abandoned everything and flew back to Asmara. I have never seen wedi Amer since.

The book’s narrative does not shield the student movement from criticism, but shows its tragic nature. The method Dr Bereket employs is not escape, but engagement, helping the reader to identify with the era and its tragedies. The story conveys or explores a truth that we Eritreans in particular buried as part of a bygone era.

From the first page, which begins with the birth of a child who is then abandoned, the narrative unfurls through a series of flashbacks. Time magically coils backwards and forwards. Reading the book, I was constantly surprised, although I was familiar with many of the episodes, by the way these caught me unawares time and again. The distant past is present in every moment as the future is portrayed with ambiguity. Important shifts in the narrative’s time sequence reflect a reconstructed reality that is almost surreal. Certain events dramatically dance as others simply hop around the reader’s imagination. Dr Bereket cleverly situates certain events in the present day even as time gradually winds through generations. I was caught in that dance of dances. Once again, he managed to restore the magic and mystery of that long-gone era of the Ethiopian revolution.

I left Addis Ababa in 1975/76, a year after the tikuru qidamye (black Saturday) of the November 1974 massacre of 60 government officials. The Red Terror campaign started a couple of years later. The Addis I left behind was exciting. While there, I had had fun like a fitaH kurkur would (like a puppy dog that has suddenly found its freedom) – I had visited café bars, strolled in the famous piazza, frequented parties like there was no tomorrow. At the same time I remember visiting Eritrean political prisoners who were flown in from Asmara at Alem-beqagn, the notorious prison that witnessed unimaginable horror. But things were becoming more and more ominous in front of my eyes. The dusk-to-dawn curfew did not deter me, a typical teenager, from living life to the fullest. The EPRP members I met were young recruits who roamed the bars visited by young people, but I never liked them because they used to corner me with questions regarding the Eritrean issue.

Now we have an Eritrean personality writing the story of EPRP and MEISON via well-placed characters who lived through that time. This alone will raise the question of why someone of Dr Bereket’s stature chose that particular subject matter. I understand his position because he lived in Ethiopia through that turbulent period. The important thing is that he is convincing the reader that he/she has to dream again. Bridge-building is not that difficult if one believes in magic. Is the author suggesting an alternative framework of struggle through bridge building? Is he ‘banking on the magic of reason and sanity to give peace a chance’?

My favourite character in the book is Saba. ‘From the time when she was a 14-year old student activist and budding revolutionary, to the time when her generation became engaged in a life-and-death struggle as opposed political forces fought for dominance, marked by occasional breakout of violence’ she is a firm and poised figure.

Another strong character in the story is fiery Gebrekristos who advocates for the disadvantaged citizens of Eritrea in Ethiopia. When the leaders of Union of Veteran Fighters for Justice tell the young activist that they have empathy with his crusade, the young man explodes.

“Empathy! A whole generation of people, all young, are wasting their lives in miserable conditions...Empathy! Thank you very much, your Excellency. I must tell you with great respect that your Union is missing a historic opportunity to do the right thing. I cannot become a member of your Union when its leading members are not ready to fight for justice now. I wish you well!

I could literally hear his footsteps as he stomped out and slammed the door behind him. Gebrekristos’s story is both interesting and intriguing, although I found the emotional intensity that his argument aroused in me uncomfortable. His thoughts towards Eritreans are uniquely progressive. The reality of Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia ‘induced a crisis of conscience in Gebrekristos causing him to reassess his previous officially sanctioned idea about citizenship and identity’.

The Ethiopian and Eritrean struggles for freedom were, and will always be, conjoined through the course their respective youth pursued. How can one not reflect on the current situation of the region at this junction of our history? When will Ethiopia, as a host country, ever acknowledge the importance of embracing those precious young Eritreans and properly look after them until better days come to Eritrea?

In order to gain insight on his rationale for writing Deliverance, I exchanged a few emails with Dr Bereket while writing this review. A paragraph, which is worth quoting, fascinated me. He said: ‘Let us try to be part of the solution, for I think we are in the cusp of change as far as Ethiopia is concerned. And change in Ethiopia will lead to change in Eritrea, I am convinced’.

The book is available at Red Sea Press.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)