Eritrea: From Roving to Stationary Banditry

" The control of the production of wealth is the control of human life itself " Hilaire Belloc

" The control of the production of wealth is the control of human life itself " Hilaire Belloc

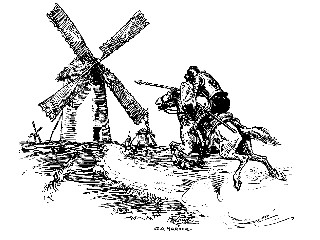

In the reputed first novel of Europe, Don Quixote the knight-errant, addled from reading numerous books of romance and chivalry, sallies forth with his nag outside the village of Mancha. The gentleman embarked upon the task of redressing wrongs and other noble duties, completely unaware that the Age of Chivalry was dead and buried for a long time. He happened to lodge in an inn but his mind conveniently took it for a castle. Though the inn keeper and lodgers were amused and shocked by the appearance of the big and gaunt person with his old and mismatched armor, they nonetheless pretended to act as he wished them. The wenches played as beautiful damsels while the inn keeper performed all the rituals required to dub him as a knight.

Having put up with all the idiosyncrasy, the inn keeper pulled his account book and asked for his money. His client however was not only moneyless but appeared completely clueless about it. Deservedly, the kind inn keeper advised the knight-wanna-be the need for food and real (the currency in Spain then) properly tied in saddle bags before launching any lofty projects of the type. Recovering his wits, our knight goes back to his village. Despite many naysayers, the Don was adamant about his intentions and soon sold his land to raise the money for his sojourn. Not only that, a squire was also employed.

Who can forget the image of the frequently rambling Don Quixote and his rotund and gregarious squire Sancho Panza, who was not only well fed but also had a flask to swig some wine from. In brief, the duo were well supplied with victuals and drinks. What is clear is that, even in a possible world (that is, in a novel), it is hard to imagine that without this principle of self sufficiency, the picaresque and fun in the big canvass of Spain would most likely not happened. It is noteworthy to remember that Don Quixote was administering his own farm lands while Sancho Panza was simply a farmer. The point is, adventure or not, both were responsible adults in their little village before they departed for the “noble” cause and both footed the bill for the cause however delusional it was from the very start.

Almost four centuries after the appearance of the book of Cervantes, several scores of armed men ventured likewise to fight for a “just cause” or to set right some wrongs in Eritrea. These are, however, not fictional characters but natives of the former empire of Italian Africa. Like the characters in Don Quixote, they seem to have been also afflicted with some kind of delusional fantasy. Clueless to the growing trends in the world, and oblivious to the cost, they nonetheless went in search of the lofty nation state that was rapidly losing its allure. But, unlike the characters in the novel, those in Eritrea launched their enterprise without taking into consideration the need for food provision and other necessities. This omission remained to leave a deleterious effect on the masses of Eritrea.

The missing elephant

Unlike Don Quixote, who quickly grasped the moment, the violent entrepreneurs in our Eritrea led a predatory roving banditry on both the pastoralists and peasants of the land. The region is largely a semi-arid zone where surplus grain production is a rare occurrence. The official historians like to point out that besides the occasional arms shipment from some sympathetic Arab state, for food and other needs, the guerrillas had to depend strictly on themselves.

What was the mainstay of this “liberation economy”? How did the humble and insecure farmers end up as “foster parents” of the multitude of armed fighters? And furthermore, what did the feeding of extra mouths do to a rural populace in the Kebessa where food is often so inadequate that the peasants have developed nuanced etiquette of eating, such as, using only “certain fingers.” As of now, study about the subject is very parsimonious. In the meanwhile, it is safe to postulate that the insurgent army, which could have possibly reached from 150 to 200 thousand during the entire ghedli period, passed the burden of the war to the precariously living rural folks.

The terrible toll exacted on the dwellers of this country has frequently been received with either denial or, in some instances, with that lame rationale of the “extreme need of war circumstances.” What is instead repeated ad nausea is the “lost opportunity” of the combatants - a clear hint that “they didn’t do it” for the peasants. The long duration of the predatory policy, which lasted for almost three decades except for few years of massive cross border food provision by NGOs, does not seem to faze many of our fellow countrymen. What on the surface may appear inexplicable has a very easy explanation: the sense of déjà vu, as a friend once remarked. The public and the entrepreneurs of violence were inured and familiar to the practices of the likewise roving courts of Abyssinia and other sultanates from the Sudanese region. The modern rebel armies did not limit themselves to ordering food and drinks but often comfortably slept in the peasants’ houses.

In the Kebessa region, there were few merabae (zinc roofed houses) adjacent to the hidmos in every village then, and these were mostly commandeered by the armed rebels. The fighters of both fronts were also not squeamish about crashing into the houses of the highland peasants. There was little corner for privacy for the poor farmers. The peasant family would often leave the merabae and hidmo premises for the fighters billeted among them and would huddle in a small corner. They almost appeared to be evicted, refugees in their own houses. The little tukuls in the lowlands were, however, left alone for the customs of the Muslims forbids the easy mingling of strange males in their living quarters. What, indeed, the behavior of these rebel movements and what legacy did they inherit from the past?

In spite of the civilization of few steles, rock hewn churches and monasteries in old Abyssinia, the life of its peasant masses was miserable and heart breaking for ages. The plow based agriculture, which was once considered advanced relative to the hoe based farming in other parts of the Continent, was however susceptible to the vagaries of rainfall and various kinds of worms and pests, such as army worms and locusts respectively. But it is not only nature that had not been kind enough to the people in the region; its rulers too highly depended on extremely extractive and depredatory practices. This observation can easily be backed with many anecdotes.

Often, in the annals of Abyssinia, an adventurer, explorer or missionary from the West arrives at the region after a hazardous journey to find his would-be host absent from the rendezvous place. The king or ras has allegedly left for a campaign to either subdue a rebellion that has mushroomed somewhere in the realm or to gather tribute. Unlike the governance in most riverine or irrigation based economies, surplus in rain based agriculture in Abyssinia was rare. The skimpy “surplus” available to the royal courts often engendered the behavior of extraction and pillage. The risky nature of the rain based agricultural economy, coupled with the heavy tax needs of kings, bred disaffection and unrest in the kingdom. The rulers in their turn were often forced to launch punitive expeditions. A vicious circle of this type of state of affairs endangers the availability of the minimum public good such as peace and law and order.

It is into this type of drought and famine prone economy, minus the few light industries in Asmera, that the rebels for liberation surfaced during our last century. Unlike our Cervantes’ characters, most of the leading personalities who remained as the leaders of the rebel movement were hot tempered university and high school students detached from the ordinary life of the peasant. What did they do for their upkeep and chow? Except for their catchy and hollow self-sufficiency phrase, we have nothing to recourse to. We have then to skip their official histories and go the round way about. A delve into the Bolivian Diary would be helpful.

Che Guevara, the icon of the student revolutionaries including our Eritrean ones, left Cuba and headed into the jungles of Bolivia in the late 60s. Unlike the left of the Asian continent and our elite in the Eritrean armed struggle, Che was more candid, open and true in what he scribbled for posterity. His upbringing in a well educated family and the liberal culture in Argentina may have influenced his behavior. His diary attests to it.

The Bolivian Diary that was made available soon after his death is not crowded out with narration of battles and skirmishes. It was instead a constant tale of the futile search for food, boredom and the resultant demoralization. Embittered by the circumstances, the gentle Doctor did not sometimes refrain from rebuking the indigenous peasants of Bolivia who, to assuage their hunger, often resorted to chewing coco leaves. The big farms or haciendas that Che was familiar with in Cuba were largely absent in the Indian lands in Bolivia and therefore no surplus to spare. Winning the hearts and minds of the impassive and suspicious Indians proved soon afterwards a futile exercise.

Food entitlement through coercion

The peasants and agro-pastoralists in Eritrea were likewise ill fed and poor like their counterparts in Bolivia. The meager access to food supply had forced many farming communities to eat only twice a day, and in some seasons famine food such as beles and the sebere have been the only life saviors, though risky to their limbs and health. This bleak scenario of our farming communities should have deterred any project that would likely disrupt or worsen the circumstances of the masses. The reign of our violent entrepreneurs, though shod only in the famous light plastic sandals, was however as chafing and even worse as the repression under the jack boots of the ordinary military juntas elsewhere in Africa. Ghedli operators did not leave us any log books to browse. Nsu, as Aklilu Zere once wrote, forbade anything of the sort. In its absence, a brief introspection of a likely everyday scenario in the Kebessa region would do the remedy.

A haili or a ganta would arrive in a village. Bypassing the chica adi, the legitimate authority, the cadre would pronto ask for the quadere. Mind you, the latter word is a bastardized version of the Italian word for the elite “cadre”, which the Italians introduced in their first colony. Though their rank is the same, the poor quadere, unlike the cadre of the guerrilla organization, is unarmed except for his ubiquitous small stick. In alacrity, the emasculated official would skitter to all the peasant households announcing the arrival of “agayesh tegadelti!” and plead for food contribution. For decades, this was an ordinary sight.

An exception to this predatory activity is the purchase of flour and other necessities from across the Sudan, and the cities to a lesser extent, by the rebels. This mostly happened in Sahel and most parts of Semhar where the density of population is thin and grain production very negligible. A caravan of camels would often sneak in and haul sorghum, wheat flour, lentils, cooking oil and always tea leaves and sugar. That the guerrillas left an enduring habit for tea among the rural populace, which considers it a luxury, tells a lot about the urban and soldiering background of the rebels.

The imperative of a sanction

The task of a rational political actor should have been to desist from any kind of violent intervention. What happened in Ancin, Indonesia, is noteworthy. When the Tsunami disaster struck the region several years ago, the leadership of secessionist rebels made a historical decision. Armed struggle, and the political program that went with it, was dropped in deference to the existence of the traumatized citizens. Such brave political acts are rare in the world and almost unheard of in our corner of the Continent.

To a rational and empathic observer, the zebene ghedli may equally be compared to zebene anbeta that time and again has wrecked havoc to peasant livelihood. It could even be considered worse. While the peasant households are likely to restock their assets after an occasional calamity such as locust infestation, the zebene ghedli was more ruinous, insidious and long lasting man made disaster. And yet, through accident in history, our political actors achieved their political objectives. Woe to him/her who dared to ask anything about property rights, contracts and the sanctity of individual rights during the ghedli years – the minimum that could be asked from a non-Hobbesian realm. Regrettably, the guerrillas in our region had an important cover to hide.

Unlike the type of rebels in Angola, who were once led by the former Savimbi, and the Ninja-like movements in West Africa, who likewise ravished their countryside, the armed political operators in Eritrea were never blessed with money raising commodities then. In Angola, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Congo, diamond and gold were not only available but were in many instances easily located for mining. Coerced labor made also their venture almost cost free. These precious mineral resources, and the complicity of the investors from the West, were particularly responsible for dragging the war in Angola. There was a benefit to it, however, in the later decades. It raised the awareness of the public in the West and mobilized political pressure on the armed organizations.

The ELF and the EPLF, on the other hand, avoided the radar simply because the grain and livestock based economy of Eritrea had no allure to the outside world. Although the grain commodity that was commandeered from the peasants was certainly as blood tainted as the diamond and gold commodities, it nonetheless did not attract any sustained scrutiny. Not even much later when the guerrillas were increasingly purloining the food brought as aid into their base areas. The guerrillas had by then perfected the art of grain requisitioning through violence and deceit. For those in doubt, what better proof than the ongoing extortion schemes on Eritreans in the Diaspora. If people living abroad several thousands of miles from the reach of the regime succumb, how would a farmer/pastoralist spare himself/herself from the armed thugs living always in his midst? The claim for “voluntary support” as advanced by some corners is disingenuous and, utmost, a fiction.

Like a car with a good transmission engine, the contemporary state of Eritrea has faultlessly transformed itself from roving into a stationary banditry. If Eritrea was to be used as a test point, this regime would prove the late political economist, Mancur Olson, who coined the famous terms of “roving vs. stationary banditry”, in the wrong. Here is a little quote from his article, Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development:

“Under anarchy, uncoordinated competitive theft by ‘roving bandits’ destroys the incentive to invest and produce, leaving little for either the population or the bandits. Both can be better off if a bandit sets himself up as a dictator-a ‘stationary bandit’ who monopolizes and rationalizes theft in the form of taxes.”

According to him a stationary bandit regime, unlike a roving bandit, has an encompassing interest to establish not only peace and order but also other public goods in order to maximize its revenue. To be fair, his theory in this instance did not dwell with the types that are not only predatory but Soviet type in inclination, an ideology shared by our fronts not long ago. Justifiably, the public in Eritrea would not see any difference between the two types of banditry.

A fundamental issue has been thoroughly missing among the growing opposition or the resistance literature. The sanctity of property rights, contracts and the environment for the free intercourse of commerce and investment that are essential for any community were either dismissed or buried under the rug. They were instead relegated to loud debates about poorly understood ideologies, political programs, the virtues of democracy and the sovereignty of the state. We have remained willfully blind to the elephant in the room, and are yet to recognize the regime for what it is: a notorious repeat offender.

It is not surprising then to find the public realm in a political paralysis. The stationary bandit in Eritrea does not only have the monopoly of violence, monopoly of taxation, but also the monopoly of the entire economy of the country, including its manpower. What we have is unfortunately not the kind of the occasional Chinese warlord in the last century who, after victoriously defeating his rivals, would retire to his lodgings and concubines and let the affairs of trade and commerce for others to mind it. The abysmal absence of a sense of outrage commensurate with the heinous theft and pillage that occurred on the semi-subsistence rural folks in the land is puzzling.

Unless the public and its advocacy groups own up to the history of predation and the pillage committed in the past, the current outrage and protest will remain weak and hypocritical. If this is not corrected, we are destined to watch all types of farces put out by the regime. The recent ones are good examples. The dictator has been lately pictured in the government media visiting some obscure places in his domain, alongside little girls with fat himbasha presenting it to him. The himbasha is probably made from the wheat flour donated from outside. So much for the self sufficiency, peace and order and other public goods from our own stationary bandits!

There is a repeating tragedy in our region: The “first colony” as the Italians used to describe Eritrea, was built under the slogan of “whatever it costs”, as mentioned once by Michela Wrong, and ended in complete disaster. Its youthful inheritors, who mostly hailed from the urban areas left by Italy, forced their own grand folly upon the public: “liberation at any cost!” And, now, not unlike the Italian case, the likelihood of the implosion of the new political arrangement is most likely.

07/08/2010

![]()

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)