A Refugee At last

I was born and grew up in Asmara, a city whose love affair never ends; it resonates in my heart in every second of my journey to seek refuge elsewhere. I have attended my primary, high school and University classes there. It is a place where I have seen my dream come true; unfortunately, it is also a place where I have seen my dream and the dream of its entire population shuttering.

I began contributing articles to the print media as young as 16 years of age. In 1998 when I was a high school student of Red Sea school (Ke’has), along with my colleagues, I co-founded a monthly newspaper called Hareg, with an aim to create a forum where students could discuss on a range of issues that concerns them. I worked as editor-in-chief of this newspaper until it was banned by the government in September 2001.

Meanwhile, as of May 2000, I began working as a reporter and columnist for the largest and the first private newspaper in the country, Setit. I contributed more than 60 articles, mostly news analysis regarding international political issues.

While I was working for Setit, along with my colleagues, I was striving hard to be the true voice of the people. However we were under constant threat and at times harassment from the government authorities. In August 2001, I was imprisoned by the government authorities for writing an investigative report regarding an unfair land allotment in the Anseba region. I was released after receiving a strict warning not to raise the issue in the media again.

After completing my high school study, I joined the University of Asmara in September 2002, where I graduated in journalism and mass communications with B.A degree in September 2007. Though I was in the University for four years, I never stopped exercising my journalistic carrier. In July 2003, I got the opportunity to work as a freelancer with the local language government newspaper Hadas Ertra. I became the first to start the international news analysis column that used to appear on bi-weekly basis. I was covering mostly regional issues and in my articles I endeavoured to remain as objective as I could. However, this was not without challenge, especially as of the beginning of 2005 when the government officially shifted its policies to anti-west and launched propaganda warfare, where I was soon to be found unfit for such a service; consequently, I got fired. Initially I was told that I was fired because of internal structural adjustment. But the truth was that I resisted their interference in my articles, as they wanted me to insult and undermine the west in general, especially the Bush administration policies in the international stage. But I resisted this interference from my boss on a number of occasions. News must be objectively covered, without any distortion of facts, and that was what I have learnt when I was trained to be a professional journalist.

When I lost my job in Hadas Ertra I had ample time to concentrate on the book that I was translating regarding modern world history and the rise of capitalism. I completed the book in June 2005 and submitted it to the Ministry of Information for censorship. Soon after, I found myself in a quagmire and underwent 35 days of imprisonment as the result. They wanted an explanation as what were my motives to translate the book. They even accused me that I was funded by the CIA. After taking the soft and hard copy of the book, they gave me a strong warning to never disclose any information about this particular incident, if not I would face grave consequences. Before my imprisonment I was also contributing articles to Eritrea profile and radio Dmsi Hafash; henceforth, I decided to quit.

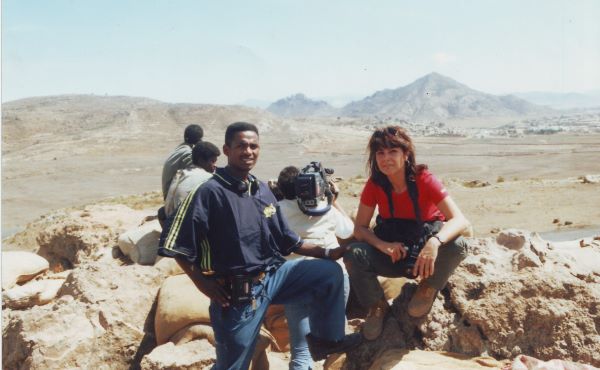

After completing my University study in June 2006, I was assigned to do my compulsory University service with the PFDJ website shaebia.org; in one way I was relieved to escape from working for the Ministry of Information, as my animosity with acting Minister Ali Abdu was at its peak then. I also felt saddened when I knew that I had to work for an organization, which is responsible for the Eritrean people’s misery. It’s ridiculous why they have chosen me to work for such an organization in the first place, which is traditionally run by the so-called amenable citizens. After all they knew my background, hence, it was a moment of a big personal and professional test for me, but I never made any compromise. It is an organization that I want to see its demise, but I found myself to do its dirty work by advocating its brutal policies, consequently my hunger for writing diminished. If they were to force me to do something without my consent, I was prepared to pay whatever price, in defence of press freedom. Even though I was fully aware of the grave consequence, I decided to remain as a professional journalist. In the one year and three months of my stay with the website. I have never been given a single chance from my boss to get out of Asmara, as he was so suspicious of me that I could leave the country in that pretext. However, I have never written a single article that lauds the government or the party itself; accidentally, I ended up being a sports reporter. In the meantime, I have never stopped from looking a way out of the hellish life with full of agony, to save myself before it was too late.

The escape

I made four failed attempts to cross the border, three times to Ethiopia and once to the Sudan. But I never gave up and succeeded with the fifth one. After six days of exhausting walk, I managed to get in to the Sudan on the 17th of November 2007 via Sawa military training camp, along two other colleagues. It was very risky and at times life threatening journey. Had it not been for one Sudanese nomad to rescue our life, we could all have vanished without trace in the deserts of eastern Sudan. The nomad named Mr. Hamid told us that just two week before our arrival, they had buried the body of two young Warsay Ykealo school students, who were presumably died as a result of water thirsty. Our fate could have not been different either, but we were so lucky to escape from that imminent danger.

Once we reached Sudan no one of us ever expected to face with such kind of agonising danger, but the nomad, who was in his mid eighties became our hero. He had to walk along with his two camels with us, in an effort to save our life. He was on foot while three of us turn by turn had to ride on the back of the camel. And it took us three days to reach a village called Girgir, 20km north from the city of Kessela. With all the difficulties of Arabic language I had at that time, but one of Mr. Hamids breathtaking expression was something that I hardly forget ‘’ Esaias ke’ab’’ meaning Esaias is a trouble maker. He also asked ‘’what have the Eritrean people done to deserve all these misery.’’ Frankly I never expected those sympathetic words to come out from such an old nomad who happens to witness the tragedy and suffering of Eritreans first hand on a daily bases.

In the town of Girgir, we were very well received by the local people, who handed us later to a plain clothed Sudanese security personal. After making the mandatory search on our body they found nothing, except four hundred US dollars. But, luckily they just took one hundred and returned us back the remaining. They gave us peanuts (they call it fuul) a stable food in the Sudan, and we ate like crazy as our belly was empty enough to receive any thing. During our journey we were only eating some biscuits with muddy water. Later in the evening, they loaded us on a lorry’s back, which was full of charcoal. Being on the top of the charcoal, every one of us had to make sure not to fall down before we reached to our dream town Kessela.

When we reached in the check point to enter Kessela, we met with two newly arrived asylum seekers and we were taken together to the security prison in the heart of the city. Kessela is a city where most of the Eritrean asylum seekers first end up before they get transferred to the nearby refugee camp. To be frank, it was a city quite less than our expectation in its modernity. The streets were rugged in many parts and the buildings mostly half completed and simply not as attractive as those in most Eritrean towns, let alone in the capital Asmara. However, it is a vibrant city, the number of cars and motor cycles in this city alone could surpass the total in Eritrea.

In the security prison we saw two girls presumably Eritrean asylum seekers, but later that night they disappeared from our sight. And we also met two members of a national service, Beyen and Mulugeta, who had an incredible story of prison break operation. Both of them were thrown in Keru’s temporary prison in suspicion of leaving the country illegally. Among other three prison mates who were held on similar charges, they were to be transferred to the bitter prison called Hadish Measker by a lorry. Two well armed soldiers were on guard one in front and the other at the back of the lorry. While in their cell, they all had agreed to escape in the middle of the way to Hadish Measker by dispossessing their guard’s guns. Beyen and Mulugheta were very instrumental in that successful operation and as far as their knowledge was concerned, their colleagues were most likely caught afterwards. No one knows for sure where they are, or simply whether they are still alive or dead, because in Eritrea in many cases escapees are subject to capital punishment by their captors.

In the detention centre, we were interrogated by the security officers, some of whom were Eritreans working with the government of Sudan, as they spoke fluent Tigrigna. They promised to transfer us to the Wedisherifay refugee camp on the next day for further assessment on our asylum case via the UNHCR. They asked us to give them money to bring us our dinner and the next morning they needed additional money for the diesel of the car that is going to take us to the refugee camp, and we gave them more money than they asked. While in Eritrea we had heard similar stories, so we were not surprised with their manner of endless money requests. One day a friend of mine, who earlier arrived in the Sudan joked in one of our online chat ‘’if you have money in the Sudan, you have everything, even if you kill the president you can set yourself free from prison.’’

However, they directly took us to the Immigration Department instead of the refugee camp. To our surprise, they began to guard us seriously just like criminals. We waited in the cell of the immigration van for eight long hours without having any idea of our fate or destiny. There was communication barrier, we could not ask them as all of us were Arabic non-speakers, and neither could they speak English as well. We could only read the seriousness of the situation in the nervous face of the immigration officials, who seem unhappy with our presence in their soil. We were hungry and angry; finally we began to complain with their manner of treatment. At four o’clock in the afternoon, two persons came and loaded us in a single land cruiser just like commodities. They later told us that they were officials working with the UNHCR and they were going to help us to get asylum in the Sudan. To our relief, finally we reached Wedisherifay refugee camp, after half an hour of drive from Kessela towards the border with Eritrea. The location of the camp is awkward for many of the asylum seekers, as you can see Eritrean hills just across a couple of miles away. I remember most of the refugees were having a sleepless night, fearing from the possible abduction by Eritrean security agents, who are believed to frequently visit the camp.

Once we reached Wedisherifay, many of the refugees came to hug and shake us, who seem surprised with our coming. Everyone was congratulating us, as if we were Olympic gold medal winners. But, as I learnt later they had a good reason to do so, as we were the first group to arrive in the refugee camp for almost a month. At that time the government of Sudan was simply returning back hundreds of Eritrean asylum seekers to the ruthless dictatorial regime in Asmara. Some of the returnees were my colleagues in the University of Asmara, who were serving in Sawa as teachers. Later I had come to learn that, had it not been for the intervention of UNHCR officials to rescue our life, our fate could have not been different. So, I should say lack was still on our side.

Wedisherifay refugee camp was mainly established to house, those who fled from the fighting during Eritrea’s war for independence (1961-1991). Most of the refugees refused UNHCR voluntary repatriation program during the late nineties to Eritrea, hence as durable solution to their problem the UNHCR was trying to resettle some of them in the western countries, but as most of the refugees already lived in protracted camp for three or four decades, they complain with the slow pace of progress in their process of relocation.

As of 2004 the UNHCR opened a new reception centre in the camp in order to assess the increasing number of new asylum seekers from Eritrea, who have escaped opposing endless slavery in the name of national service, religious persecution and ethnic oppression etc. As there is no constitution in Eritrea, there is no rule of law and this is resulted in gross human rights violation. During our arrival there were more than three thousand new Eritrean asylum seekers waiting for interview.

We were given priority in the assessment of our case, as the immigration officials have given only three days to the UNHCR for our refugee status to be determined, if we were to fail to be genuine asylum seekers, we would have certainly been deported back then. While the processing time for asylum normally takes up to two months, we finished in less than one week’s time. They transferred us to our final destination camp kilo 26, which is located almost 100km inside Sudan. Even though security wise this camp is much safer than Wedisherifay, but none of the refugees stay for more than a couple of days here, they directly opt to go to Khartoum through the help of smugglers, who find this job a very lucrative business.

I along with my three colleagues have met with a smuggler, who later assisted us to get into Khartoum illegally. Forty two people were placed in one lorry in a very overcrowded manner; we were so tightly squeezed into the lorry that, at times, we find ourselves on top of one another. We were totally covered with plastic in order to pretend the lorry was loaded with some materials. It was a tormenting journey that I barely would like to recall; we were treated like animals by the smugglers. The moment we reached Khartoum, I fell sick for a couple of days as a result of the horrible journey that lasted for two days.

Later I began to explore the taste of being in Khartoum, I felt as free as the bird for the first time in more than seven years. I loved to go from one street to another without any fear of a soldier asking me for a permit paper. I loved being myself, which I have never been in Eritrea. Above all I loved seeing most Sudanese reading morning newspaper everywhere, and I learnt that there are more than forty private newspapers in the country. For someone like me, who came from a country mini-north Korea in East Africa, I felt honoured to be among them to share their freedom. For this reason, I enthusiastically applied to work in Khartoum Monitor, a prominent English language newspaper. I worked as a freelancer for several months with a pen name, for I had to keep my profile very law. And later I ventured to publish my own newspaper in my local language called Shewit, which is the first of its kind to be published in the Sudan. Later, as it gained popularity among the urban refugees, I began to face a number of threats from Eritrean government agents. Ultimately I decided to terminate it, as I didn’t had any security guarantee from the government of Sudan. And in April 2009, I received the prestigious Hellman/Hammett award for human rights defenders in recognition of my contributions for the freedom of speech and the suffering I went through.

Khartoum is booming with massive foreign investment, the economic activity is incredible for someone who came from a capital city run by a failed government. And I marvelled at its size of nine million people, which is twice the number of the whole population of my country with 4 million.

Sudan is a transit place for most of Eritrean refugees, for further illegal migration to Libya or Egypt. I was tempted to go to Libya or Egypt but refrained later fearing potential deportation, as both countries used to extradite Eritrean asylum seekers to the dictatorial regime in Asmara. Hence, I decided to ask protection in the Sudan so as the UNHCR to assist me in resettling to any third country as the only viable option. However, I found this option very difficult and unsustainable as I had to undergo a number of complicated procedures just to secure a convention refugee status. The process was at times frustrating, as it takes extremely long time for the UN to intervene for possible solutions. Finally I have learnt how to be patient even though it was psychologically very hurting, as I was constantly living in fear of possible abduction.

My Acknowledgments

But throughout my stay in Khartoum I was never alone; I was fortunate to have the privileged support of dedicated individuals and Human Rights Organizations from Toronto to Paris, from New York to London and From Washington to Doha. With their continuous support they made me feel proud for being a journalist more than ever before.

Indeed, I have no word of thanks To Elisabeth Chirum, Head of Eritrean Human Rights Concern, whose support was like glucose to my blood. From the very moment I met her, she was treating me just like a mother; with a regular contact to know my whereabouts. Moreover, I was fascinated by her energy and dedication to the cause of Eritrean people’s suffering, in which I should dare to call her, as an icon of hope for many Eritrean refugees. Above all she has inspired me with her restless efforts and commitment in making Eritrea free from oppression and injustice. Indeed, she is one of our post independence heroes.

I also have to thank Prisca Orsonau, head of refugee’s desk at the Reporters Without Borders (RSF). She is exceptionally brilliant and very supportive woman. She had to exchange emails with me sometimes on a daily bases in an effort to address the major challenges I was facing. At the darkest moments of my life she was sharing all my pains from thousands of miles away. I am really proud to have her support; without her my life could have gone horribly wrong.

Elisabeth Wichel, head of the journalist’s assistance program of the Committee to protect journalists (CPJ) and her assistant Karen Philips were also extremely supportive as they were rendering me their badly needed assistance. Their continuous follow up and advices made me stay strong as a refugee.

I should also thank Aaron Berhane my former boss, now Editor in Chief of Meftih newspaper in Canada, from the bottom of my heart. He has showed me the light at the end of the tunnel, not only when I become a refugee, but since I was in the belly of the regime six years back. Over the last years of his exile, he has proved to me that he is a friend in need. Above all he has shaped my life as a journalist in many ways and I am very grateful for all his support.

I would also like to extend my thanks to Lidia Tabtab from the Doha Center for media freedom, to Marcia Allina from the Human Rights Watch (New York) and to Carol Sparks from the UNHCR Khartoum. Of course I can’t name them all but I would like to thank everyone for standing beside me in the most challenging period of my life.

Now I am in Norway, enjoying freedom that I badly missed at home over the past nine years, and it is a place, where I hardly imagined finding myself as a refugee, but I am here starting a new life with dignity that I barely get in my country. Even though I am far away from home, the imprisonment of my colleagues, the continuous cycle of suffering of our people inside and in the refugee camps is constantly resonating in my mind, to break my absolute ecstasy, but, my pen is still my weapon.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)