Refugee radio voices for a new Eritrea

It's 6.55 on a Monday evening in Melbourne and, under fluorescent lights held together with duct tape and on creaky office chairs, Osman Shihaby, Berhan Jaber and Ahmed Ali are about to do something that in their home country would get them killed.

It's 6.55 on a Monday evening in Melbourne and, under fluorescent lights held together with duct tape and on creaky office chairs, Osman Shihaby, Berhan Jaber and Ahmed Ali are about to do something that in their home country would get them killed.

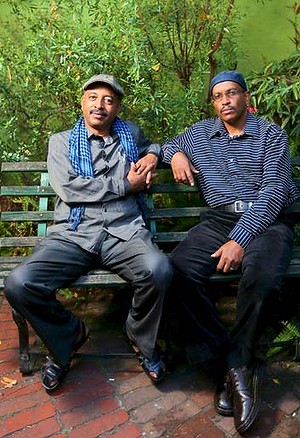

Osman sits on one side of the desk, arms stretched out flat before him. His dark hair is cropped short and his moustache neatly trimmed. He's a man used to making himself invisible. He sits completely still. Opposite him, Ahmed scribbles vigorously on his pile of notes. He runs a finger over the neat lines of Arabic script before him, moving his lips in preparation for delivery.

Beside Osman, Berhan is leaning back in his chair. He delicately crosses his legs, smoothes his black linen pants and adjusts his woollen cap. As Ahmed hustles beside him, he looks to the wall as if to a distant view and smiles.

The three men are sitting inside 3CR headquarters, and as the sky turns from grey to the bluish night-time tinge, the sign on the wooden door of Studio One changes from white to red and spells out those two dangerous words - ON AIR.

Osman, Ahmed and Berhan, all refugees from war-torn Eritrea, are producers of Eritrean Voices, and every Monday night they make radio. Their program is one of many around the globe being produced by Eritreans in the diaspora who are using their microphones and voices to agitate for change in a country that has been labelled the ''world's largest political prison''.

The show begins every week with a news report. And as soon as he gets the thumbs up from Osman, Ahmed sets off like a sprinter, delivering a steady flow of headlines into the microphone.

Today, he is talking about the events that have led to the nation's current dire circumstances. On September 18, 2001, when the world was focusing on September 11, President Isaias Afewerki's government shut down what was Eritrea's entire free press. Six privately owned newspapers were dismantled and all the directors, editors and journalists were imprisoned.

Ahmed begins today's broadcast by listing the names of those who were imprisoned that day - 11 journalists, as well as 11 government ministers. ''They're all assumed dead,'' he says grimly.

Since then, Eritrea's civil liberties have been systematically dismantled and journalism has been under sustained attack. It is a situation that for the past seven years has landed Eritrea in last place on the so-called ''Press Freedom Index'', which is compiled by non-profit organisation Reporters Without Borders and charts media independence across 180 countries. The 2014 index was released this month, with Eritrea again in last place.

Back in Studio One, Ahmed is interviewing Berhan, who has just returned from a year in Sudan where he visited refugee camps interviewing displaced Eritreans.

Berhan's voice is gentle, throaty. He uses his hands to illustrate where he has been, painting a virtual map in the air, on the table, his long fingers dancing, his voice rising and falling with each gesture.

Berhan knows from experience the risks faced by those who stay behind - and the danger he presents to his own family by speaking out, even from 12,000 kilometres away.

''Every month,'' Berhan says, ''more than 700 Eritreans cross the border. In east Sudan today there are half a million Eritrean refugees. In Ethiopia - 350,000.''

Berhan says that inside Eritrea there is ''no freedom of movement, freedom of speech or freedom of information''. This means that if the electricity is shut off, or if there are food or water shortages, which there regularly are, citizens have no way of finding out why.

The absence of media, he continues, is incredibly disorienting, disempowering, and psychologically damaging. Leaving, too, is perilous. ''The army at the border have got shoot-to-kill orders … If they capture you while you are running, it's a bullet in the head.''

In the years leading up to the 2001 crackdown, those who had already left Eritrea, such as Berhan, watched as the situation deteriorated. But, Berhan recalls, despite what they were hearing from relatives back home, there was little critique of government actions and a culture of silence among Eritreans in the diaspora.

That culture existed, he says, largely because of fear. ''People were so brainwashed, they thought [that] even if they were in Australia, even if they travel to the moon, President Afewerki could bring them back and imprison them.''

Also, Eritreans in the diaspora who spoke out sometimes risked persecution from local supporters of the Eritrean government. Berhan is patently aware of that risk. When he started broadcasting, complaints from some quarters soon turned to death threats.

Then, in 2007, when Berhan interviewed some key defectors, he says he received a phone call. It was his sister calling from Eritrea to tell him that their mother had been put in prison. ''We don't have any problem with your mother, but tell your brother to shut his mouth,'' authorities had warned.

After three months, Berhan's mother was released, but she continues to suffer chronic pain from being tied up under arrest.

Some in the local community have bridled as a result. ''People come to me and say, 'Stop it! You're putting your mother at risk, your sister at risk.' But I tell them, 'All Eritrean people - we are at risk.'''

This, Berhan says, is where radio programs such as this one being produced in Melbourne come into effect. Eritrean Voices was inspired by similar enterprises such as Awate.com, an Eritrean news site based in San Francisco and founded by Saleh Gadi. During the years leading up to 2001, Gadi was living in Kuwait writing reports criticising Eritrea's decision to go to war with Ethiopia. In response, Gadi claims, he was ostracised. The Eritrean government cancelled his passport, leaving him stateless.

Gadi eventually received amnesty in the US. Once settled, he wanted to build a media source among the diaspora that challenged the pro-government voices dominating the discussion. Gadi agrees with Berhan that there is a strong government hand in what happens across the world wherever Eritreans live, and ''a lot of intimidation''.

''The Eritrean government have infiltrated every community in the world and have networks of supporters everywhere who threaten people and, either directly or through relatives back home, punish them for speaking out,'' he says.

Gadi launched Awate.com, whose mission statement is ''Inspire, Inform and Embolden'', to challenge that power.

It was within this same tradition that Berhan started Eritrean Voices more than 10 years ago, in part to model a democratic culture for Melbourne's Eritrean community.

Having lived in a closed society for much of their lives meant people were not only afraid to speak their minds, Berhan notes, but that they didn't know how. ''The show is a way to look into that fear and train people for democracy,'' he says.

''If we don't train ourselves now, when this regime changes, democracy's not going to come. So while you are in school you have to learn it and practise it. And the school is Australia, America, Canada, wherever Eritreans are living.''

With that principle in mind, says Berhan, Eritrean Voices is produced with a strict charter of independence. Each week, the show reports on events inside Eritrea and updates listeners on what's happening in Melbourne's Eritrean community.

The programmers regularly invite guests who represent government interests and encourage listeners to call in and offer their opinions. In this way, the show demonstrates what an independent media looks like, and how people can speak out if they so choose.

The Eritrean consulate declined to comment for this story.

In their studio, Berhan and Ahmed continue their discussion about Berhan's trip to Sudan. They are speaking in a fast-paced Arabic punctuated frequently with English ''OKs'' and ''all rights''.

Ahmed has come straight from work and beneath the desk he taps his pointy dress shoes as he talks.

''When people come from Eritrea to Sudan,'' says Berhan, ''all of them have run away from a prison. They've suffered a lot. They've been beaten. They are all psychologically damaged. And when they arrive in Sudan, they say, 'Where have we been?'

''Even though Sudan is not a democratic nation it's much better than Eritrea. So once they get the chance to listen to radio or read a newspaper, they get a real shock. They say, 'We were not living. We were alive, but we were dead.'''

Berhan says that the show encourages Eritreans to pressure world governments to force political reform in Eritrea.

His dream is to build a bridge between the diaspora and Eritreans inside the country to implement change directly. There are now radio stations, he says, using satellites to beam their shows into Eritrea.

One day, perhaps, Eritrean Voices will join them.

This story was found at: http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/refugee-radio-voices-for-a-new-eritrea-20140315-34tpj.html

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)